Aerial survey but especially magnetic prospection has thrown up entirely unexpected results.

At present it is possible to recognize two main blocks of the sample transect within which we have collected large-scale contiguous magnetic data, one in the south-west and the other to the north-east. The block at the north-east, discussed here, is so close to the town of Rusellae that it could be viewed during the city’s lifetime both as a suburban and as a rural area.

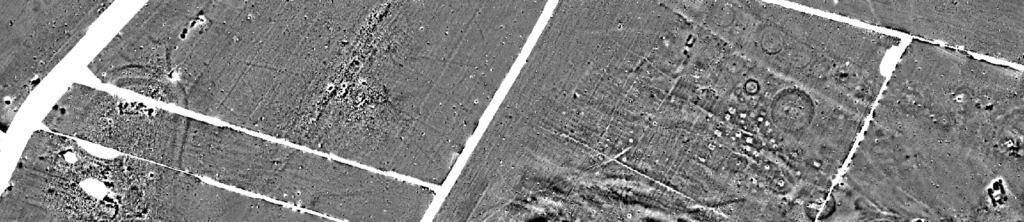

Close below Rusellae itself, in an area of superficially undistinctive arable landscape, there is clearly visible a mass of magnetic anomalies representing a major road connecting the countryside with the city, bounded on both sides magnetic data showing a dense concentration of ring-ditches and rectangular anomalies that can without doubt be interpreted as burials, in effect the remains of a major cemetery probably dating to both the Etruscan and Roman periods. At present 34 ring-ditches and 37 rectangular anomalies have been recognized and mapped. On the basis of comparative studies on other Italian contexts such as Cerveteri (Tartara 2003) this is clearly a major and previously unsuspected funerary landscape placed along one of the main roads entering and leaving the city of Rusellae. Moreover on the southern (lower) edge it is possible to recognize another road and a peculiar structure showing as a round anomaly surrounded by a square of opposite magnetic polarity; the shape, articulation and size of this feature finds a convincing parallel in Roman mausolea.

This interpretation one could envisage the interesting scenario of a funerary landscape with a degree of continuity from as early as the 7th or 6th centuries BC to some time in the Roman period, perhaps with detectable links to the various stages already demonstrated in the internal structure of the city. Significantly, but surprisingly in the light of the geophysical evidence, neither micro-morphology nor past field-walking survey had suggested the presence of this important and apparently long-lasting funerary landscape.

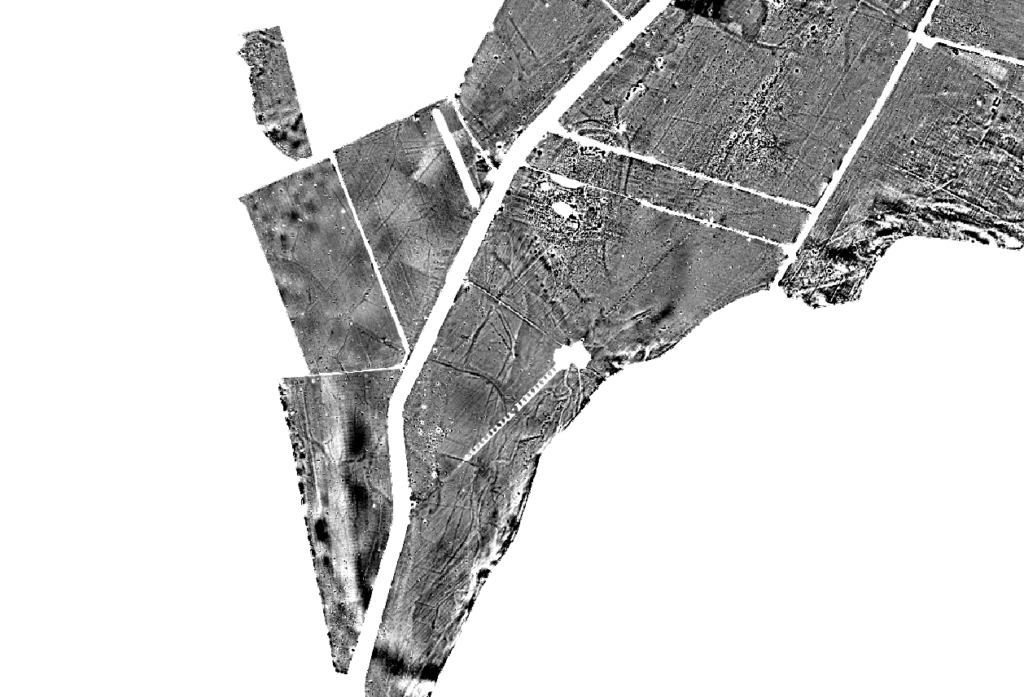

A few hundred meteres to the south-west the magnetic data shows a dense concentration of anomalies that can be readily interpreted as man-made functional elements and natural features within the local landscape: field systems, cultivation patterns, road systems, buildings and geomorphological features. Another interesting discovery takes the form of a double-ditched enclosure, close alongside the present course of the river Salica. The enclosure was first identified in the magnetic data and then confirmed by intensive field-walking survey.

Within the 0.8 ha central area of the enclosure there were several magnetic anomalies that coincided with intense artefact scatters, the size and shape of which suggested interpretation as buildings. A larger east-west anomaly at the north might even represent a church. In this case field observation and artefact collection were critical in identifying key features of the site: a significant variation in elevation (of as much as 1.5 m) matching the features visible on the magnetic map, and artefact scatters clearly indicating a medieval dating, probably within the 10th to 12th centuries.

What appears to have been revealed here is a previously unsuspected artificial mound or alternatively a settlement occupying a slight natural eminence within the local topography. Moreover, in the neighbourhood of the site, but mostly to the west of the river Salica, magnetic anomalies revealed a dense pattern of field boundaries, roads and palaeo-riverbeds. The outstanding character of the magnetic data and local topography prompted the implementation a borehole survey and an intensive programme of fieldwork based on artefact collection within a virtual grid of 10 m x 10 m ‘cells’, aimed at establishing the chronological range and function of the site and at providing a more detailed picture of the match between the magnetic measurements, micromorphology and artefacts distribution. The survey and the analysis of artefacts set out in showed a quite distinct pattern of intensive human activity deriving predominantly from the early 10th to early or mid 12th centuries AD. On the basis of comparative studies of shape, size, morphology, artefact assemblage and chronological range this site can confidently be interpreted as a medieval settlement that shares significant characteristics with four others identified during recent survey work in or close to the Grosseto lowland. It is certainly possible, moreover, that the adjacent field system and road could be associated with the same cultural context and chronological range. The parcels within the field system are characterized by a relatively consistent pattern of size, shape and boundary-type. The boundaries were clearly ditches, no doubt serving to divide the land into functional sub-units while at the same time providing indispensable drainage for arable land close against to the river Salica. A comparative study based of size, shape and relationship between the field system and the ditched enclosure tends to support the interpretation as a medieval settlement and related field system showing clear resemblances to sites on the Tavoliere in Puglia revealed in the first instance through aerial photography: Casone San Severo, Motta della Regina, Masseria Petrullo and San Lorenzo in Carmignano, for instance, all display a quite close resemblance in general appearance to our field system in terms of size, shape and overall pattern, and in some cases also to the shape of the settlement itself.

Two other of these newly identified enclosureslie within the 25 km2 area of the sample transect, of which 15 km2 consists of valley lowland, including 4 km2 so far subjected to intensive survey. This represents a density of one such settlement for each 1.3 km2 of the closely examined area. A larger area of the landscape will need to be covered before such a statistic begins to become truly meaningful but this rate of recovery is nevertheless significant in that over the past 40 years the archaeological development of Tuscany during this formative period of history has been intensively studied by traditional means, including excavation and field-walking survey, notably by archaeologists from the University of Siena, especially under the leadership of late Prof Riccardo Francovich. A key concept resulting from this work has been the long-term development of hilltop villages, or ‘incastellamento’. Despite all of this work very few settlements of any kind had been identified in lowland Tuscany before 2005, and none of the type now coming to light in the Rusellae area.

The discovery of this unexpected category of settlement is bound to stimulate discussion on how to integrate this new information into the historical concepts of ‘incastallemento’ in ways that will improve our understanding of landscape transformations in the centuries between Late Antiquity and the mature Middle Ages, not least in the interplay between the strength and strategies of the ruling classes and the continuing existence of functioning communities and settlement patterns within the Tuscan countryside.

Perhaps we could envisage a new scenario for landscape transformation in this immediate area. The enclosure alongside the river Salica could prompt interpretation as the result of at least two different processes. If we interpret the presence of few early medieval sherds as residual artefacts, the settlement could then be considered as a new foundation of the early 10th century rather than the outcome of a longer-term process of the kind envisaged within the ‘incastellamento’ model. In that case it would be possible to suppose that at this time the ruling classes invested resources in developing new settlements on the fertile lowland, perhaps moving the population from elsewhere. On the other hand, if – as the author would prefer – we interpret the presence of a small amount of early medieval pottery as deriving from a first phase of development initiated by some sort of community already living in or around this area, then the social and economic process could have been quite different. The answer to such speculation could only come from excavation, preferably on a fairly extensive scale.

The settlement and in particular the field system illustrate an extraordinary vital stage of a society that had the capacity and/or need to reorganize settlement and landscape patterns, perhaps removing almost all vestiges of older patterns in the process. As a final remark in this context we should perhaps emphasize the complexity of the area under investigation. Past studies identified this as one of the most important areas within the Grosseto plain for agricultural production. The present phase of landscape survey has produced clear evidence of a high level of hydrogeological instability in this part of the local landscape. Therefore, the creation of this new settlement and field system, whether financed initially by the ruling classes or undertaken of their own volition by an existing rural community, would have required advanced know-how of the local area, along with social resources in terms of labour and productive capacity, in order to fulfill the project in the first place and to keep it working as a viable social and productive concern over time.